The Surprising Reason Your Partner Doesn't Support Your Dreams

And Why That Might Be A Good Thing

One of the biggest fights my partner and I ever had centered around an extremely common relationship plea: Why don’t you support my career as much as I want you to? If you love me, if you are committed to our relationship, shouldn’t you be all in on supporting my dreams?

Relationship science consensus used to state that the more committed someone is to their relationship, the more they will support their partner’s goals. Therefore, a lack of support was considered a sign of low commitment. I believed in this view, so I wondered if my partner’s doubts signaled that my relationship was doomed.

Fortunately, the relationship science has changed, and it turns out my point of view can sometimes be completely wrong. It can actually be a good thing for your partner to be less than fully supportive of your goals. Let me explain why.

When Love Leads to a Lack of Support

What is known as The Manhattan Effect reveals a relationship paradox: sometimes when a partner is highly committed to your relationship, they won’t be supportive of goals they view as threats to your union. In other words, their lack of support might actually signify how invested they are in preserving what you've built together.1

Once my partner and I dug into this issue ourselves, we learned this was indeed the case. While I thought my partner’s lack of support for my venture was due to her lack of investment in the relationship, she was actually highly invested, and worried I was getting pulled away from the partnership we’d worked so hard to build.

Having observed this dynamic, I decided to investigate whether other couples experience this same issue. It turns out, many do. When I interviewed 100 couples where one of them was an entrepreneur, I expected a clear pattern: I assumed the strongest couples would have a life partner who supported the entrepreneur’s business fully. Instead, I talked to many couples where the opposite was true. In some of the strongest relationships, partners actively and regularly pushed back against business demands—not because they didn't believe in the entrepreneur, but because they could see how the venture was pulling their partner away from the relationship.

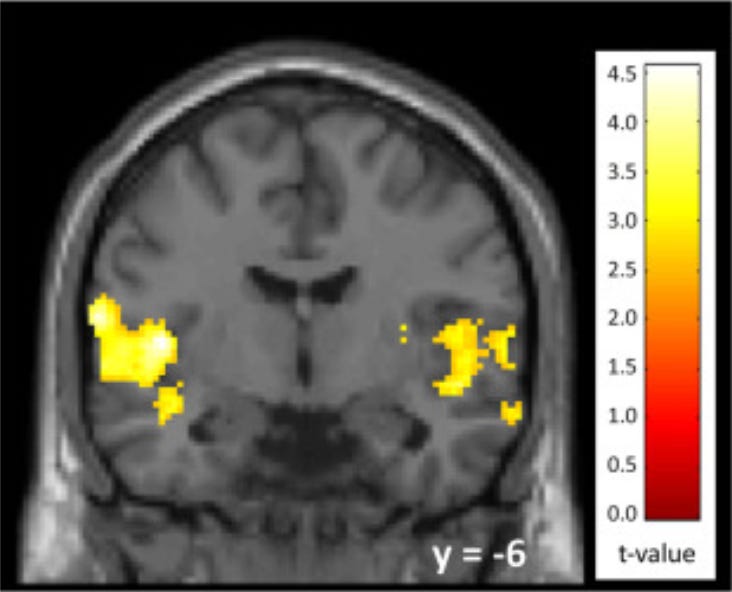

These partners had reason for concern! Entrepreneurs don't just like their businesses—they can be downright obsessed with them. Brain scans show that when entrepreneurs talk about their ventures, the same neural pathways light up as when parents talk about their children.2 Entrepreneurs work longer hours, have greater stress,3 and yes—do often see their businesses threaten their relationships. As I found in my interviews, a wise partner doesn't just cheer from the sidelines; they help protect what matters most by pushing the entrepreneur to balance their business with their personal life.

Make the Manhattan Effect Work for You

You may someday be in a situation where you feel your partner isn’t fully supporting your business or career path. This is what you should do.

The first step is to notice if this conflict—lack of support for one partner’s goals–is playing out in your relationship. Then, determine which role you are playing: if you are the one feeling unsupported, or the one withholding support. Some researchers have hypothesized that having better awareness of your own role in the relationship is the first step to any relationship solution, so you need to know how you’re contributing to the dynamic.

Once you are aware of the dynamic, there are three promising paths forward:

Have an honest conversation about how the goal may compete with your relationship and what boundaries can limit that competition. That might deactivate your partner’s fear and reframe the goal as something that is actually a source of good for both parties.

If you are the partner opposing the goal, create time for a stress-reducing conversation to provide emotional support and stress relief without actively coaching, advising, or endorsing their goal. This will help your partner see you as an ally in facing the goal together, without you getting too involved. This is called non-intrusive goal support,4 and it is strongly associated with improved relationship outcomes.

If you are the partner feeling unsupported, share why support for this goal is important for you, and specify what kind of support you are looking for, whether it’s guidance, affirmation, or just a listening ear. Then, ask what routines, rituals, or other changes you can create together so that they don’t feel like your ambition is detracting from their happiness and the relationship’s health.

Looking back on that fight with my partner, I realize we were both right. I needed support for something I cared deeply about. She needed to protect something we both cared about even more. Understanding this dynamic didn't just save our relationship—it made us better partners.

The next time your partner isn’t supporting what you want to do, pause before assuming they don’t believe in you. While untangling this dynamic will take work, you may find you have the greatest gift of all: a partner who is truly committed to you and your relationship and is primarily focused on making it last.

Hui, C. M., Finkel, E. J., Fitzsimons, G. M., Kumashiro, M., & Hofmann, W. (2014). The Manhattan effect: When relationship commitment fails to promote support for partners’ interests. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 106(4), 546–570. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035493

Lahti, T., Halko, M.-L., Karagozoglu, N., & Wincent, J. (2019). Why and how do founding entrepreneurs bond with their ventures? Neural correlates of entrepreneurial and parental bonding. Journal of Business Venturing, 34(2), 368–388. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2018.05.001

Shane, S. A. (2008). The illusions of entrepreneurship: The costly myths that entrepreneurs, investors, and policy makers live by. Yale University Press.

Feeney, B. C. (2004). A secure base: Responsive support of goal strivings and exploration in adult intimate relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 87(5), 631–648. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.87.5.631