Fall in Love With Who Your Partner is Becoming

How small moments of support shape who your partner becomes

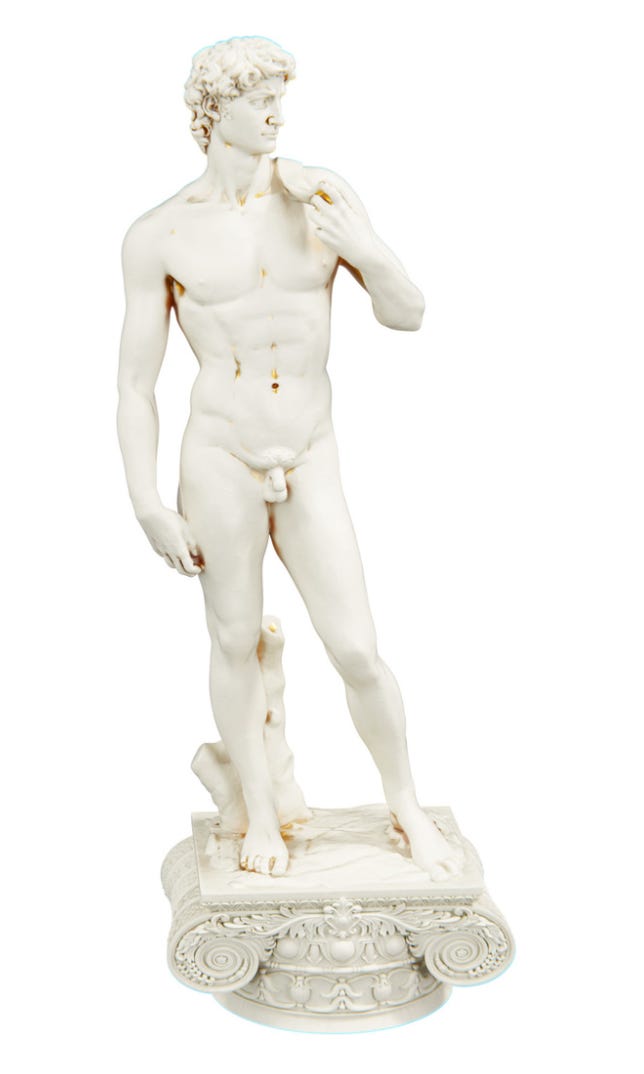

Michelangelo’s David is more than just arguably the most famous sculpture of all time.1 It’s also the inspiration for one of the most important processes in relationships.

While David was first completed in 1504, its history far predated that. It was carved from a block of marble quarried in 1464, and at least two sculptors tried to work with it before eventually quitting. The block then sat untouched in the elements for a quarter of a century, with no other sculptor touching it until Michelangelo took on the commission in 1501.2

Michelangelo took a decidedly different approach that may have been the key to his eventual success. Rather than trying to impose his will on the marble and perfect it, he fell in love with the flaws of the block and worked to see the perfection within those imperfections.

This is the important lesson: arguably the most famous statue of all time was only made because the artist fell in love with its flaws.

The Michelangelo Phenomenon

In a relationship, we are often encouraged to see our partner in a positive light. While this has merit,3 it may be even more important to know what “light” our partner wants to be seen in. Rather than trying to idealize our partner, what happens if we focus on recognizing their own vision of who they want to become?

This is where Michelangelo comes in. The Michelangelo Phenomenon occurs when someone understands who their partner wants to become in the future (their “ideal self”) while affirming and non-intrusively supporting behavior aligned with their vision. For example, if one person wants to be more present, their partner could notice when they naturally put the phone down (“I loved how you were with me just now”) and support opportunities for more presence (e.g., leave our phones in a drawer for a walk) without trying to control their choices.

The Michelangelo Phenomenon is associated with two powerful outcomes: first, one partner’s affirmation and support predicts the other partner’s movement toward their ideal self (as reported by both parties); and second, it is connected to stronger relationship satisfaction and commitment.4

Of course, embracing this requires actually working to understand what your partner views as their ideal self, rather than imposing your own ideal vision onto them. If you do the latter, there’s actually a name for that as well: The Pygmalion Phenomenon, which is associated with a range of negative outcomes on personal and relational wellbeing.5

In a world so often obsessed with self-optimization, it is powerful to pause, get curious about who your partner wants to become, and support each other on your journeys.

Falling in Love with our Flaws

So how can we, like Michelangelo, make our own relationship into our own version of David? Think of it as personal development without a self-centered lens: rather than thinking about what you want and focusing on where you want to go, focus on who your partner wants to become and how to consistently affirm and support their progress.

My favorite way to do this is a simple, 5-question activity which makes for a great date night conversation.

The Michelangelo Conversation

This is a series of five questions, which can be covered in 30-60 minutes of distraction-free conversation.

#1) What Is An Ideal Self Role You Want To Work On? Choose a role you play in life–partner, parent, child, sibling, boss, whatever–where you intrinsically want to grow in the coming year (not one where you feel pressure to perform).

Example: I want to focus more intently in my role as a parent this year.

#2) What Is Your Ideal Self Aspiration In That Role? Describe in one sentence what an observer will see or experience if you achieve your desired growth in this role.

Example: My son will see me as an attuned parent who praises his strengths and efforts, facilitates his growth by engaging his interests, and supports healthy boundaries while always loving him (all feelings and needs are valid, not all behaviors are).

#3) What Are Your Ideal Self Traits? Identify three traits that will help you achieve this growth. Briefly share how each trait can help you to move towards your aspiration (#2).

Example:

Curiosity: I want to ignite my curiosity around my son’s current world and interests. When an activity aligns with learning for me, I stay engaged at a much deeper level.

Intentionality: I want to revisit my intention to be present and attuned with my son when I am with him. The fact that I run the childcare calendar can sometimes cause me to (gulp) think of time with my son more like a task to be managed, rather than time to enjoy.

Creativity: With a little bit of creativity, I can often find a more enjoyable and stimulating activity for each of us.

#4) What Is Your Ideal Self Goal? Brainstorm one small, repeatable goal that makes concrete progress toward becoming your ideal self.

Example: Whenever I have my son for more than one hour one-on-one, I will brainstorm at least 3 specific activities to do during our time together, and let him choose what we do.

#5) What Is Your Ideal Self Affirmation? Once you’ve laid out this goal, ask your partner to share one specific moment from the last month where you behaved in alignment with your ideal self aspiration (#2) and/or traits (#3). Have them share what you did, when it happened, and the positive impact. After they’ve responded, be sure to say “thank you” to your partner and then switch roles.

Example: My wife, Anna, kindly shared that “Cameron does a great job of tuning into Ian during morning wake up routine by engaging in funny banter and playtime with Ian’s favorite songs and toys to facilitate waking up and getting dressed and ready for school!”6

When we understand who we truly want to become, and recognize who our partner wants to become, we can realize one of the greatest joys and opportunities in a relationship: facilitating a life of growth by falling in love with each other’s flaws. It worked out well for Michelangelo, so why not try it out for yourself?

Other candidates include The Great Sphinx of Giza (Egypt), the iconic Moai (Easter Island) statues, Auguste Rodin’s The Thinker, The Statue of Liberty, The Monument to Procrastination, The Pillar of Passive Aggression, and The Memorial to Reply-All Emails.

The original commission was for a student of Donatello (not the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtle), Agostino di Duccio (1464-1466). Later Antonio Rossellino tried and also gave up (1476).

https://www.britannica.com/story/how-a-rejected-block-of-marble-became-the-worlds-most-famous-statue

Murray, S. L., Holmes, J. G., & Griffin, D. W. (1996). The self-fulfilling nature of positive illusions in romantic relationships: Love is not blind, but prescient. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 71(6), 1155–1180.

Rusbult, C. E., Finkel, E. J., & Kumashiro, M. (2009). The Michelangelo phenomenon. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 18(6), 305–309.

Same as above

She wasn’t paid for providing this content!